![poldi climbing into the cockpit]()

Leopold Wenger, Jr climbs into the cockpit of his plane as he talks with his mechanic. In April '43, Poldi was made squadron leader.

copyright 2014 Wilhelm Wenger and Carolyn Yeager

Translated from the German by Carlos Whitlock Porter

4 January 1943: We had some very strong wind and monstrous sea swells in the past few days. Heavy surf on the coast, like you hardly ever saw. I didn’t even celebrate New Year’s Eve at all this time. I was already in bed by 22 hours, since we wanted to convey our New Year’s Best Wishes to the tommies really early in the morning. But once we got outside on New Year’s Day, you couldn’t fly at all, the weather was so bad. So on the 2nd we bombed a small town, Knightbridge, until there was not much left of it. I took really good photographs during this attack. We were over there again yesterday. This time it was Shanklin’s turn to get it, a city on the Isle of Wight. The flak was quite accurate, but too late. Once again, we got good photos of the attack.

![Knightsbridge deep attack_1-2-43]()

A deep attack was made into Knightbridge on Jan. 2nd (above) and on Jan. 3rd, Shanklin (below). Photos from Poldi's on-board camera.

![Shanklin deep attack_1-3-43]()

11 January 1943: Yesterday around midday, we attacked Teignmouth, a city on the southern coast of England, with heavy bombs. The effect was enormous. Whole rows of houses flew through the air. Unfortunately a good comrade of mine failed to return from this combat sortie. We hope he ended up in captivity. (According to the casualty list, it must have been Feldwebel Joachim von Bitter, shot down by a Typhoon of the 266th Squadron).

9 February 1943: Back from furlough. I got here about 5 hours and hit the sack right away, slept until breakfast. Although they roused me, I overslept. This trip was more comfortable than the last. I got a connection in Linz right away and a good seat. I kept watch in Schallerbach and actually saw the Hotel "Austria", where Mom stayed last summer. I also got a connection in Paris right away and went on to Rouen by fast train; but there I had to wait three hours. So I was able to call Caen and there was already someone waiting for me there, at the railway station. So I got back just exactly on time, three hours before I was supposed to start service. Not much has changed here. A few new faces and a few of the old ones stayed away. They’ve got a beautiful plane for me, so everything is all right.

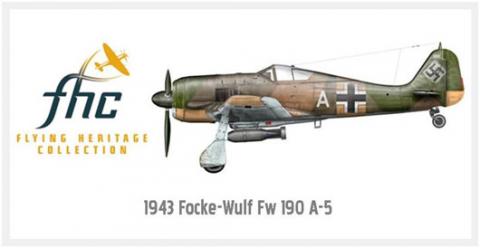

14 February 1943: So I’ve got a new plane now (Fw 190 A-5 ). First I had to break it in for myself and drop practice bombs on a target area. Then it was back to work, over there. Yesterday I delivered my “business cards” on my official visit there. This time it was Dartmouth’s turn. We surprised them so much that the tommies never even had time to sound the alarm when they saw us. So the streets were very lively; very active anti-artillery fire and barrage balloons.

![Fw 190 A-5]()

17 February 1943: Yesterday afternoon I flew back to England and gave Kingsbridge another good bombing. While I was doing it, I could very easily see the destruction left over from our last mission. There wasn’t much flak. This morning, we followed suit with a bigger squadron towards Shanklin on the Isle of Wight and gave them a good beating. They seemed to be very surprised, but their flak was very accurate during our approach.

23 February 1943: We had thick fog a few days ago, and our military activity was restricted to exercises, sports and education. In the evening, we sat down together as usual and chatted about all kinds of things. As I often do, I went to the cinema yesterday evening. I bought the book "Anilin" at the Front bookstore in town. I was on radio on the 19th, during the Front Reports. I also got a phonograph record from them. I’ll play it when I get back home again.

23 February 1943: Today, I’m sending Dad the first small package with a ½ kg of solid glue. Will that be enough for Dad? I’m already looking around for some silk for Mom. I’ll buy it when I get back in town again.

28 February 1943: Since the weather is still so bad, we haven’t gotten a lot of flying done! We only got active again on the 26th. We attacked the city of Exmouth; it was a hard mission. I’ve seldom seen such accurate anti-aircraft fire as this time. But the city got a really good “Thank “You” message. At the same time I blew up a gas tank and shot up a moving train, hard. I was able to take some really good photographs while doing it.

However, once again, we unfortunately had some losses in the dog fights that followed the attack. (According to the casualty list, Feldwebel Hermann Rohne and Unteroffizier Kurt Bressler were shot down in aerial combat with 2 Spitfires and 4 Typhoons from the 266th Squadron, 80 km south of Exmouth).

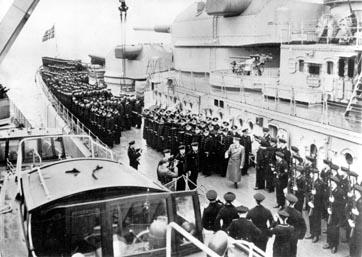

12 March 1943: After writing to you yesterday morning, I again take up my pen to let you have the latest news of the events of the past few hours. We are now a few hours away from our home port. We flew a very heavy attack with many planes yesterday against the city of Hastings. It was a large-scale attack with all the trappings. The English flak was especially active. There were a lot of fireworks and finally some hard aerial combat.

Today, this morning, at dawn, we started at 7 hours, on the dot, to carry out a reprisal. I saw the roofs of the English capital cityfor the first time. But London was clouded in fog, so that you could hardly see a couple of kilometers at low level. Their anti-aircraft batteries weren’t even firing at all, but there were a lot of English fighter planes. Just as we were flying back, the sun came out, red-red, and rose high over the ocean; what a beautiful sight, but we had relatively little time to enjoy this natural wonder in its full glory, since we had some very hard aerial combat.

16 March 1943: On the 14th, I flew a mission against the [south] eastern coast of England, attacking the railway station of the city of Clacton-on-Sea (north of the mouth of the Thames), destroying it with a direct hit. (According to the flight logbook, taking off from Vizernes, approximately 50 km from Coxyde).

The attacks we’ve flown in the past few days were some of the heaviest these English cities have experienced lately. Even the tommies admit this. Of course, it wasn’t child’s play for us, either, since their defenses were extremely heavy. You can’t describe the results of an air attack in words, so I won’t even try. You can see just how tough it’s getting by all the bullet holes in our planes and our own losses.

Willy already thought we’d have a tougher time of it over there – as even Little Moritz [slang for “a child”] can understand – but just leave everything to us. For the moment, he’s already happy to see the flak of our own defenses, and he wrote to me that he wanted to join the Air Force Auxiliary Personnel and be stationed in the Rhineland or somewhere around there. When I read that, it makes me mad. How often have I told him – and he can see proof of it all around us, wherever he looks – that he has to finish school first. A few days later, he got the idea that he wanted to join the infantry and be stationed on the Eastern Front. Let’s hope he gradually gains a bit more sense and will decide once and for all, what he really wants to do. I’ll write about something else now, otherwise I’ll get even madder!

19 March 1943: Our squadron commander (Captain Heinz Schumann) got the Iron Cross today. He earned it a long time ago and we’re all happy for him.

24 March 1943: After a few days of very unfavorable weather, it finally cleared up so as to allow to fly a heavy attack against Ashford, the most important railway junction northwest of Folkestone. It’s not very often I get to observe the effects of the bombs going off the way I could today. They were all direct hits. I was flying second string and received some heavy flak, too. One plane exploded next to me in the air. A light artillery piece fired a shell right in front of my nose as I was diving, and tore the sheet metal off my engine, leaving a hole in my wing. Butber, my wingman, was right there on the spot and knocked out the gun in an instant. Then a gas container exploded and so much debris went flying through the air that it was a pleasure to see. As we flew away, one single cloud of smoke hung over the entire city.

_________________________________________

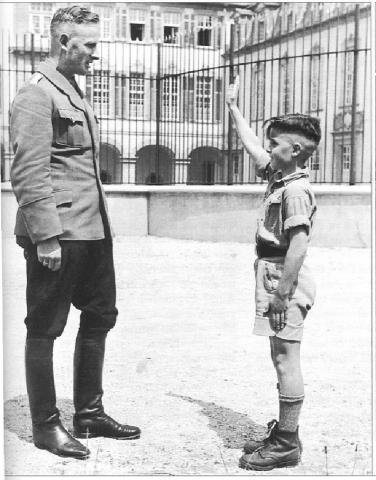

Poldi becomes squadron leader ...

The captain has since become group commander, was granted a furlough and wrote the following letter to my brother while on furlough -WW:

Dear Poldi,

I assume that Bunny has now reported for duty as an adjutant with Peltz (at 28 years of age the youngest general in Germany) and that you’re in charge of the whole she-bang now, that is, on the condition that the Reichsmarschall has approved the exact plan with the group that Peltz wanted to suggest to him. But I assume that anyway. As Major Grammas has probably informed you, you would then get the whole squadron.

Although you’re a little bit young for it, I recommended you anyway, and I assume that you’ll run the whole show forcefully and efficiently; lieutenants as squadron commander are no rarity these days. I also did it in the interests of the squadron, since I’d like to see a new man in charge for a change. The squadron has been decimated by this deployment and your big job, and Nippa’s, too, will be to obtain replacements. But with Radlewski, Eschenhorn, Pfeiler and maybe Basil, too, of whom I'm not informed yet, remaining – that should be possible. As a flier, you know better than I what it’s all about, and you have more experience than I do in fighter-bomber warfare. The main thing, in my view, however, lies somewhere else. What good is a squadron with fantastic pilots, if they lack a certain something. And that certain something, Poldi, is something that only the squadron commander can supply, if they can’t supply it for themselves. You have to make the men understand that it doesn’t matter to a soldier whether he dies or not. Maybe this is putting it a bit crudely, since we all like to live, of course, but you have to have at least a willingness to die. But I don’t want to try to give you too many lessons, since I’m entrusting you with the squadron I’ve grown so fond of, precisely because I assume that you have that attitude.

Apart from that, I’m having a damn good time on furlough and I’m enjoying my family. I still have a few favors to ask of you, Poldi: please send a voucher for a shirt and trousers for my uniform.

2. some cigarettes

3. some onions and butter and maybe something else to eat. There’s not much to eat around here.* And let me hear from you soon! Please thank Müller especially, who is probably taking care of Strolchi [the Squadron dog]. Is Eckleben back yet? [He had been on furlough.]

Best wishes and good luck

Yours, H. Schumann

*The food situation is already critical in some parts of Germany.

_______________________________________________________

4 April 1943: It’s Armed Forces Day today, and for this reason, even the English paid us a visit today, trying to drop bombs on our heads during lunch. Two English bombers got shot down.

I’ve flown two attacks since we got back here (to Caen): on 1 April we attacked Ventnor, where again, I took a couple of photographs this time, and yesterday, a big attack on the city of Eastbourne. Although we caught them napping on the 1st, we came under a lot of English anti-aircraft fire yesterday. On the 1st, I shot up a moving automobile travelling along the country road until it caught fire.

![Ventnor Ap1-43_before "raising"]()

Ventnor immediately before the attack, April 1, 1943, and after the attack (below)

![ventnor after the attack]()

Yesterday, we had to put some of the anti-aircraft positions out of action with our cannons and machine guns before we could attack the city. In doing so, I received three direct hits in the the fuselage and tail of my plane. These must have been the last three shots that gun ever fired, though, since my cannons did a nice piece of work on it. Our bombs were very effective. Very shortly after the attack, the whole town was cloaked in smoke and grime. Unfortunately, my plane was so badly shot up that it crash-landed in the sea shortly before we reached our own coastline.

![Eastbourne - 4-3-43]()

Eastbourne on April 3, 1943 (above and below)

![4-3-43 Eastbourne]()

We finally got magnificent spring weather today, very good if you want to go walking, but too good if you have to go on a mission. The park is beautifully green. I wonder what it looks like in Germany? Perhaps I'll make it home again in the summer, what do you think?

8 April 1943: It was really hot during the last few missions, every time. We attacked the biggest city on the Isle of Wight yesterday, Newport. But we dropped all our bombs under heavy flak, and they all scored direct hits. Unfortunately, another two of us got shot down. (According to the casualty list, it must have been Uffz. Günter Eschenhorn and Uffz. Rudolf Radlewski). On the way back, we had to deal with a few English fighters (Typhoons) and came home bathed in sweat. The missions aren’t getting any easier, quite the contrary, but our reprisals are making themselves felt, as the English themselves admit.

14 April 1943: We’re receiving frequent visits from "the other side" now. They attacked us twice yesterday afternoon, in two equal attacks. But apart from a few window panes, there wasn’t much damage. At the same, some pretty fierce and hectic dogfights between English and German escorting fighter planes took place right over our heads. This was the first time I was able to observe planes getting shot down while watching from the ground. For our ground personnel it was really something. They do nothing but get our planes ready for action, after all, and they take great care to make sure everything is working as it should. But they were never able to participate in our successes personally. So they cheered like mad at every Spitfire they saw spiralling down and exploding in flames.

![pipifax]()

Poldi's mechanic Gefreiter (Aircraftman 1st Class) Thielen, affectionately known as "Pipifax."

10 May 1943: We haven’t flown any missions in the last few days, but we’ve been in the air a lot, mostly practice missions, testing various kinds of new and different and smaller bombs, almost always dropping them at low altitude or practice attacks on paratroopers; a type of maneuver. The weather is sometimes very good, but there’s a big storm going on now, sometimes with gusts of about 100 km per hour wind. It’s unbelievable the way you get knocked around by these gusts in a plane.

![pullover sweaters]()

I had to go pick up my squadron pullover today. That’s a white woolen sweater with our squadron insignia, the red fox, on the left breast; they look very good. At any rate, only four of us are supposed to wear it at first, since they were lent to us by a committee. You’d think they had nothing better to do, but it‘s great fun anyway.

One of us got the German cross in gold today, naturally it had to be celebrated as it deserved, and did we!

16 May 1943: Nothing new on the Western front, you might say. That’s the way it’s been with us; in any case, we haven’t flown any missions. But in exchange we went through several aerial attacks recently. Just yesterday, I had just gotten to town and was at the Front book shop, when our position was attacked again. My office looks like hell. But overall most of the damage is slight. We’ve been having up to three air alerts a day sometimes; mostly false alarms. But whatever we’re not doing now, we’ll make up for it when the time comes.

18 May 1943: We had to endure a whole series of heavy attacks in the past few days. We were lucky nothing worse happened, but it’s a miserable feeling to lie there in the dirt and be unable to defend yourself when they’re shooting all around you.

23 May 1943: After a long period of inactivity we flew a few large-scale attacks again today and I was one of the first ones there with my squadron (I’ve been made squadron leader in the meantime). The attack on the city of Bournemouth was very effective, we dropped large numbers of bombs and did a lot of damage. Of course, the English flak tried to get a word in edgewise but we answered back smartly with our cannons and machine guns. We were pursued by four Spitfires but there was no aerial combat. This attack made a big impression on our young aviators in particular, and they were appropriately enthusiastic. We were unfortunately not in a position to celebrate properly with cakes and coffee, because we’ve got to be ready for action, but we’ll make up for it when we get a chance.

![Bournemouth 7_5-23-43]()

Attack on Bournemouth on May 23rd (above and below) - notice the smoke.

![bournemouth 3]()

I got a magnificent fur vest as a present from a well-known major (Heinz Schumann) a short time ago. I’ll send it home some time.

25 May 1943: We made a surprise appearance back over on the other side of the Channel with a big squadron of planes today about noontime, and attacked the city of Brighton with heavy bombs. In doing so we blew up two gas works with a total of five gas containers. Those were some real fireworks, I can tell you! You could see the black pall of smoke far out over the ocean. The flak was very accurate though, but we got off with surprisingly little damage and we shot them up quite nicely with our cannons.

![Brighton7_5-25-43]()

The city of Brighton on May 25th (above) and the Gas Works (below) which Poldi and his squadron blew up.

![Brighton Gasworks]()

29 May 1943: The 25th of May attack on Brighton must have done a lot of damage, since the English are still screaming about it today. They paid us a return visit today, we really had to hit the dirt. It made a lot of noise, of course, but when it was all over the damage wasn’t half as bad as we had feared at first. In any case, we suffered no casualties and that’s the main thing. Next time we pay them a visit, it’ll be a different story, we’ll really give it to them.

1 June 1943: About noon day before yesterday we carried out a very heavy attack against Torquay. As with every large-scale attack, we really gave it to them. The English flak was really up to scratch, and gave us a hard time. Then we had some aerial combat, first with English, and then American, fighters. I left a good comrade behind on this mission, too. We’ve taken our revenge, though! Yesterday morning, the tommies tried to tear up our position. Once again, we hit the dirt, and when everything was all right again and we had put out the fires, we could see that really there wasn’t too much damage.

![Torquay 7_5-30-43]()

The pictures from Torquay on May 30th (above and below) are very clear but don't show the damage done.

![Torquay_5-30-43]()

So to pay them back for their little visit, we paid them another courtesy call, with a big squadron, just for company. Just as we got to the English coast I saw a 4-motored flying boat. We shot at it, but didn’t have any time to stick around, otherwise we would have given them a good hiding. We had our bombs to drop, after all. Then the fun started. At St. Catherinas Point (Isle of Wight) I scored a direct hit on a fuel or ammunition warehouse. In any case, the whole kit and kaboodle blew up with huge jets of flame. We then attacked a couple of targets with cannon and machine gun, and raked a radio station. The flak was a bit lively and shot at us as we flew away. English fighter planes came up after us, but were too late. In any case, this mission was one we all enjoyed; anyhow we did our job for today.

![Lighthouse encounter 6-1-43]()

Encountering the lighthouse at St. Catherine's Point (above) on June 1st mission, and also a British plane (below).

![6-1-43 encountering a British plane]()

4 June 1943: We attacked Eastbourne again about noon today, with heavy forces, flying low level, doing considerable damage, although the flak was shooting significantly better than usual. I received a 2 cm direct hit behind the motor, putting a hole all the way through the plane. Several of my instruments quit working and I got a little splinter in my right lower thigh which remains there, someplace. First I felt a violent impact, and after that I had enough to worry about just with my wound, but I was able to get home safely.

![eastbourne 7_ 6-4-43]()

A 2nd mission against Eastbourne on June 4th; in the picture below smoke can be seen rising in several locations.

![Eastbourne 2_6-4-43]()

I’m taking photographs on each mission now, and will send the pictures home when I get a chance. Our park is very beautiful now, only the grass has grown too high, but nobody around here cares about that.

14 June 1943: Dear Mother! I would like to wish you all my love and fondest greetings, and I hope you will be able to celebrate this birthday very many times yet and in good health. I would also like to express my belated best wishes to my little brother [Gerhard Adolf], who proudly celebrated his “Fourth Jubilee” a few days ago. I completely forgot to wish you a joyful Pentecost, but I only noticed it was Pentecost when other people told me about it. Anyway I hope you enjoyed a very happy couple of days during the holiday.

Everything is all right with me here, only there’s a lot to do. Day before yesterday, we had yet another heavy English air attack. Two English bombers were shot down in flames by our flak. No casualties here. I hope all is well with you. Now, dear parents, heart-felt greetings from your Bibi.

N.B (last letter from France).

****************************************

The mission on 4 June 1943 was also Poldi’s last combat flight on the Channel coast and the letter to his mother dated 14 June 1943 was the last one from France, since he was transferred to Sicily on 15 June 1943. To be continued ....

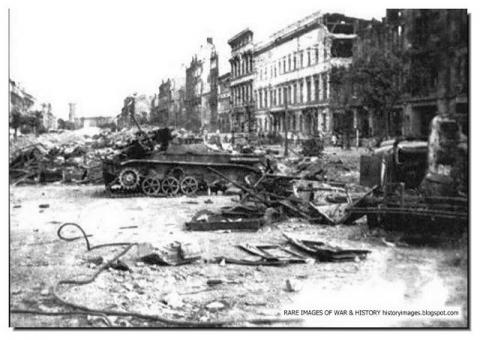

Pretty soon I reached the main road South. I walked through Oranienburg and Sachsenhausen and arrived dead tired at the edge of Berlin, in Tegel. (Note that Seelow is east of Berlin close to the Oder River. Willy is back where he began. -cy) I was surprised when a young, well-attired man addressed me, asking if I were a former soldier on my way home. He introduced himself as a Lutheran priest helping homeward-bound soldiers. At a small villa, I met a lot of other ex-soldiers; we were fed, slept in a bed and next morning we could even take a shower bath. A hearty breakfast and some pocket money were handed out and, with a goodbye, we were sent on our further way. Indeed, a very unusual treatment.

Pretty soon I reached the main road South. I walked through Oranienburg and Sachsenhausen and arrived dead tired at the edge of Berlin, in Tegel. (Note that Seelow is east of Berlin close to the Oder River. Willy is back where he began. -cy) I was surprised when a young, well-attired man addressed me, asking if I were a former soldier on my way home. He introduced himself as a Lutheran priest helping homeward-bound soldiers. At a small villa, I met a lot of other ex-soldiers; we were fed, slept in a bed and next morning we could even take a shower bath. A hearty breakfast and some pocket money were handed out and, with a goodbye, we were sent on our further way. Indeed, a very unusual treatment. Early in the morning, everyone pushed to get a place in the rail cars. We passed through Jüterbog, which I had marched through two month ago, and arrived in Wittenberg on the Elbe river. I tried to cross the river over the bridge but the Russian border guard drove me back. My idea to reach the West through the U.S. zone to Bavaria failed. Some of us were thinking to swim across the Elbe river, but gave up the idea when we were told the Russians were cold-bloodedly shooting at everybody who tried.

Early in the morning, everyone pushed to get a place in the rail cars. We passed through Jüterbog, which I had marched through two month ago, and arrived in Wittenberg on the Elbe river. I tried to cross the river over the bridge but the Russian border guard drove me back. My idea to reach the West through the U.S. zone to Bavaria failed. Some of us were thinking to swim across the Elbe river, but gave up the idea when we were told the Russians were cold-bloodedly shooting at everybody who tried.